A chiropractic subluxation often relates to the spine and its connecting structures.1 Chiropractic subluxation assessment generally involves evaluating the pathophysiological consequences of the central segmental motor control problem;4, 12 these may include pain, asymmetry, biomechanical or postural changes (such as changes in relative range of intervertebral motion), changes in tissue temperature, texture and/or tone, and other findings that can be identified using special tests.12Once identified, subluxations are corrected using a variety of techniques including high velocity low amplitude chiropractic adjustments, instrument assisted adjustments, and lower force manual techniques and approaches.13

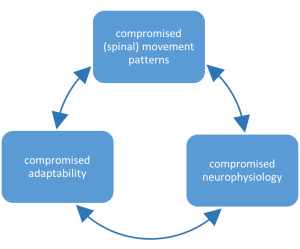

A growing body of scientific evidence has demonstrated that spinal function impacts central neural function in multiple ways,3, 4, 14-19 and that improving spinal function has an impact on clinical outcomes.20-24 Scientists have known for several decades that neurons continuously adapt in structure and function in response to our ever-changing environment.25-27 This ability to adapt is known as ‘neural plasticity’,27 and it is now well understood that the central nervous system can reorganize in response to altered input.28-35 Examples of increased sensory input[1] that can lead to neural plastic changes include repetitive muscular activity 29, 36-41 such as typing or playing the piano, or repeated tactile sensory input such as occurs with blind Braille readers.42 Similar central nervous system change or reorganization may take place due to a decrease in behavior or activity.[2] 32, 43-49 Thus the concept, that alterations in paraspinal muscle function due to abnormal spinal movement patterns are capable of changing central neural function is totally congruent with current neuroscience understanding, as well as current scientific findings.3, 4, 14-19

[1] In the scientific literature, this can be known as hyperafferentation. Hyper–meaning increased, and afferentation – meaning the afferent nerves, which are the ones that go to the brain with information.

[2] In the scientific literature, this is often called deafferentation.

References

1. Hart J. Analysis and Adjustment of Vertebral Subluxation as a Separate and Distinct Identity for the Chiropractic Profession: A Commentary. J Chiropr Humanit. Dec 2016;23(1):46-52.

2. Rosner AL. Chiropractic Identity: A Neurological, Professional, and Political Assessment. J Chiropr Humanit. Dec 2016;23(1):35-45.

3. Haavik H, Murphy B. The role of spinal manipulation in addressing disordered sensorimotor integration and altered motor control. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Apr 5 2012;22(5):768-776.

4. Henderson CN. The basis for spinal manipulation: chiropractic perspective of indications and theory. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Oct 2012;22(5):632-642.

5. Stephenson RW. Chiropractic Textbook. Davenport, Iowa: Palmer School of Chiropractic; 1927.

6. Practice Guidelines for Straight Chiropractic. Paper presented at: Wyndham Conference; May 13-17, 1992, 1992; Chandler, Arizona, USA.

7. Association of Chiropractic Colleges. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Position Paper # 1. July 1996. . ICA Rev. 1996;November/December.

8. Lantz CA. The Vertebral Subluxation Complex PART 1: An Introduction to the Model and Kinesiological Component Chiro Res J. 1989;1(3):23-36.

9. Gatterman MI, Hansen DT. Development of chiropractic nomenclature through consensus. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Jun 1994;17(5):302-309.

10.Leach RA. The chiropractic theories: a textbook of scientific research. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004.

11. Owens E. Chiropractic subluxation assessment: What the research tells us J Can Chiro Assoc. 2002;46(4):215-220.

12. Triano JJ, Budgell B, Bagnulo A, et al. Review of methods used by chiropractors to determine the site for applying manipulation. Chiropr Man Therap. 2013;21(1):36.

13. Cooperstein R, Gleberzon B. Technique systems in chiropractic. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 2004.

14. Uthaikhup S, Jull G, Sungkarat S, Treleaven J. The influence of neck pain on sensorimotor function in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. Nov-Dec 2012;55(3):667-672.

15. Haavik H, Murphy B. Subclinical neck pain and the effects of cervical manipulation on elbow joint position sense. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Feb 2011;34(2):88-97.

16. Pickar JG, Bolton PS. Spinal manipulative therapy and somatosensory activation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Oct 2012;22(5):785-794.

17. Pickar JG. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spine J. Sep-Oct 2002;2(5):357-371.

18. Treleaven J. Sensorimotor disturbances in neck disorders affecting postural stability, head and eye movement control. Man Ther. 2008;13(1):2-11.

19. Branstrom H, Malmgren-Olsson EB, Barnekow-Bergkvist M. Balance performance in patients with Whiplash Associated Disorders and Patients with prolonged Musculoskeletal Disorders. Adv Physiother. 2001;3:120-127.

20. Martinez-Segura R, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Ruiz-Saez M, Lopez-Jimenez C, Rodriguez-Blanco C. Immediate effects on neck pain and active range of motion after a single cervical high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation in subjects presenting with mechanical neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Sep 2006;29(7):511-517.

21. Ozkara GO, Ozgen M, Ozkara E, Armagan O, Arslantas A, Atasoy MA. Effectiveness of physical therapy and rehabilitation programs starting immediately after lumbar disc surgery. Turk Neurosurg. 2015;25(3):372-379.

22. Hawk C, Khorsan R, Lisi AJ, Ferrance RJ, Evans MW. Chiropractic Care for Nonmusculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review with Implications for Whole Systems Research. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(5):491-512.

23. Ruddock JK, Sallis H, Ness A, Perry RE. Spinal Manipulation Vs Sham Manipulation for Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Chiropr Med. Sep 2016;15(3):165-183.

24. Holt KR, Haavik H, Lee AC, Murphy B, Elley CR. Effectiveness of Chiropractic Care to Improve Sensorimotor Function Associated With Falls Risk in Older People: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. May 2016;39(4):267-278.

25. Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. 4 ed: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2000.

26. Brown TH, Kairiss EW, Keenan CL. Hebbian synapses: biophysical mechanisms and algorithms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:475-511.

27. Cooke SF, Bliss TV. Plasticity in the human central nervous system Brain. 2006;129(Pt 7):1659-1673.

28. Fratello F, Veniero D, Curcio G, et al. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by paired associative stimulation: reproducibility of effects and intraindividual reliability. Clin Neurophysiol. Dec 2006;117(12):2667-2674.

29. Tyc F, Boyadjian A, Devanne H. Motor cortex plasticity induced by extensive training revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation in human. Eur J Neurosci. Jan 2005;21(1):259-266.

30. Sessle BJ, Yao D, Nishiura H, et al. Properties and plasticity of the primate somatosensory and motor cortex related to orofacial sensorimotor function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. Jan-Feb 2005;32(1-2):109-114.

31.Kaelin-Lang A, Sawaki L, Cohen LG. Role of Voluntary Drive in Encoding an Elementary Motor Memory. J Neurophysiol. February 1, 2005 2005;93(2):1099-1103.

32. Weiss T, Miltner WH, Liepert J, Meissner W, Taub E. Rapid functional plasticity in the primary somatomotor cortex and perceptual changes after nerve block. Eur J Neurosci. Dec 2004;20(12):3413-3423.

33. Tinazzi M, Valeriani M, Moretto G, et al. Plastic interactions between hand and face cortical representations in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a somatosensory-evoked potentials study. Neuroscience. 2004;127(3):769-776.

34. Sanes JN, Donoghue JP. Plasticity and primary motor cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:393-415.

35. Liepert J, Bauder H, Wolfgang HR, Miltner WH, Taub E, Weiller C. Treatment-induced cortical reorganization after stroke in humans. Stroke. Jun 2000;31(6):1210-1216.

36. Yahagi S, Takeda Y, Ni Z, et al. Modulations of input-output properties of corticospinal tract neurons by repetitive dynamic index finger abductions. Exp Br Res. 2005/02// 2005;161(2):255-264.

37. Renner CI, Schubert M, Hummelsheim H. Selective effect of repetitive hand movements on intracortical excitability. Muscle Nerve. Mar 2005;31(3):314-320.

38. Schubert M, Kretzschmar E, Waldmann G, Hummelsheim H. Influence of repetitive hand movements on intracortical inhibition. Muscle Nerve. Jun 2004;29(6):804-811.

39. Byl NN, Merzenich MM, Cheung S, Bedenbaugh P, Nagarajan SS, Jenkins WM. A primate model for studying focal dystonia and repetitive strain injury: effects on the primary somatosensory cortex. Phys Ther. Mar 1997;77(3):269-284.

40. Byl NN, Melnick M. The neural consequences of repetition: clinical implications of a learning hypothesis. J Hand Ther. Apr-Jun 1997;10(2):160-174.

41. Nudo R, Milliken G, Jenkins W, Merzenich M. Use-dependent alterations of movement representations in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. J. Neurosci. January 15, 1996 1996;16(2):785-807.

42. Pascual-Leone A, Torres F. Plasticity of the sensorimotor cortex representation of the reading finger in Braille readers. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 1):39-52.

43. Tinazzi M, Rosso T, Zanette G, Fiaschi A, Aglioti SM. Rapid modulation of cortical proprioceptive activity induced by transient cutaneous deafferentation: neurophysiological evidence of short-term plasticity across different somatosensory modalities in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(11):3053-3060.

44. Murphy BA, Haavik Taylor H, Wilson SA, Knight JA, Mathers KM, Schug S. Changes in median nerve somatosensory transmission and motor output following transient deafferentation of the radial nerve in humans. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114(8):1477-1488.

45. Murphy B, Dawson N. The effects of repetitive contractions and ischemia on the ability to discriminate intramuscular sensation. Somatosens Mot Res. 2002;19(3):191-197.

46. Hallett M, Chen R, Ziemann U, Cohen LG. Reorganization in motor cortex in amputees and in normal volunteers after ischemic limb deafferentation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;51:183-187.

47. Tinazzi M, Zanette G, Polo A, et al. Transient deafferentation in humans induces rapid modulation of primary sensory cortex not associated with subcortical changes: a somatosensory evoked potential study. Neurosci Lett. 1997;223(1):21-24.

48. Brasil-Neto JP, Valls-Sole J, Pascual-Leone A, et al. Rapid modulation of human cortical motor outputs following ischaemic nerve block. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 3):511-525.

49. Brasil-Neto JP, Cohen LG, Pascual-Leone A, Jabir FK, Wall RT, Hallett M. Rapid reversible modulation of human motor outputs after transient deafferentation of the forearm: a study with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 1992;42(7):1302-1306.